The second Tuesday in November is the biggest day of the year on Grand Manan Island: Trap Settin’ Day. This is the start of lobster season, the day when people can put their lobster traps in the water for the fall fishery. I suppose that, strictly speaking, lobster season actually starts the next day when fishermen are allowed to haul their traps and sell lobsters.

But it is the 7:00 a.m. roar of all the diesel engines pulling full loads of lobster traps away from the various Island wharves on this second Tuesday that gets the adrenaline pumping for those who follow this livelihood on the sea. Each fisherman has his own idea of just where he wants to set traps to catch lobsters, so as soon as 7:00 a.m. is proclaimed, it is a race to the favourite spots for that first chance at that special piece of ocean floor.

I can remember many years ago when I was doing a lot of diving, one of the wily old fishermen from the Island port of Ingalls Head would quiz me up intensely on where I had seen lobsters and what were they doing? He tried to be coy and nonchalant about his enquiries, but he wasn’t fooling anybody. I wasn’t a lobster fisherman, so I had no problem giving him all the information I could. Nevertheless, I had to chuckle at his intensely competitive effort to try to be the high-line fisherman for his port.

Of course in the many years of diving, I did happen to make some observations, and passed along a tip to a fisherman who mentioned to me just last year that he has followed that tip for years and it has proved to be solid advice and given him good results. But to allow him to continue with that edge, I won’t share the tip in this blog. And anyway, each fisherman has his own theory on lobster habits and movements gained from years of experience and observation, so let's just watch the season unfold and play out as it has for generations.

This year a friend of mine found himself shorthanded for the labour-intensive first week of fishing, so he asked me if I would come fishing with him for the first week. I really hadn’t planned on it, but thought “Why not?” So here I am fishing for a week. And I am savouring the very essence of Island life, the working life on the water. And speaking of essence, I really don’t mind the smell of lobster bait, but I have been given strict orders at the home front that any clothing article smelling of lobster bait cannot come past the garage.

Today would have been "Trap Settin' Day", but due to forecasts of strong northeast winds, the fishermen met together yesterday and with consensus among them decided to postpone the start of the season, to await more favouable weather. This collective wisdom and cooperation is refreshing and cause for hope; it wasn't many years ago when fierce independence and competitive ambition would have prevailed and some fishermen would take unnecessary risks to get traps in the water, forcing the rest to participate in the race, whether they wanted to or not.

So, kudos to the fishermen for being willing to cooperate, to postpone their own rewards for a few days so that all might participate in a safer fishery.

Even at Our Cove, which is sheltered by islands all around, the easterly had whipped up little breakers on our rocks, so the conditions are probably quite nasty out in the open sea.

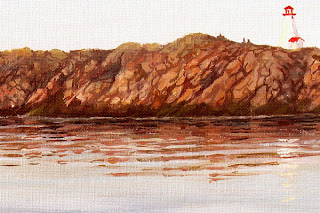

For this “trap settin’ day”, I have chosen to feature the print “Gannet Rock Afternoon”. The view depicted here would have been quite familiar to scores of Grand Manan lobstermen, who would fish these waters that look upon Gannet Rockand its lighthouse. I say “would have been”, because the painting depicts the lighthouse before it was fully automated; now, with no one living on the rock, some of the buildings have been removed.

This year, the wind today and forecast for the next few days is strong northeast, exactly the opposite of the wind direction depicted in the painting. Nevertheless, the painting “Gannet Rock Afternoon” does give a feel for the life and work of lobster fishing.